whitehot | Interview with Anna Ayeroff

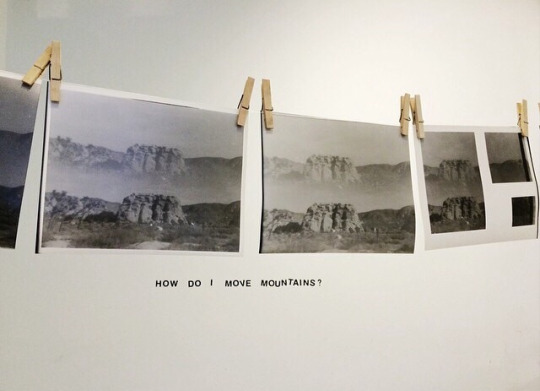

Installation view of “Clarion Calls”, including from left to right:

“A Brief History: Clarion, Utah”, Slideshow, 80 35mm slides in slide carousel, “If I could live here, I would”, Mylar and Thread

“I built a shanty and I lived there for three years”, Hand-cut chromogenic print and Mylar

Courtesy, ICI and the artists

Anna Ayeroff and Alex Harvey: 100/10Δ1

Institute of Cultural Inquiry

1512 South Robertson Boulevard

Los Angeles, CA 90035

Through 17 June 2011

A. Moret speaks with Los Angeles based artist Anna Ayeroff about her recent exhibition Clarion Calls at the Institute of Cultural Inquiry.

A. Moret: Your exhibition is the first in the 100/10 series at the Institute of Cultural Inquiry (ICI) represented with the title 100/10Δ1. As the assistant director of the ICI, could you speak to the inspiration behind the project and its intended impact?

Anna Ayeroff: The 100/10 (100 days/10 visions) project is meant to both reveal and enact the creative process. For 100 days, 10 visual researchers – artists, writers or visual thinkers – will work in our “laboratory” space, interacting with and investigating the ICI Earth Cabinet, Ephemera Kabinett and the 2,500+ volume library. The 10 visual researchers are asked to play with ideas, blending contemporary visual practices with aspects of the ICI archive. In exposing the process and creating a dialogue about it, the project becomes more about ideas and less about objects. The goal is to inspire discussion and creation and to get away from the show and tell nature of a traditional display.

Moret: A key component of 100/10 is the dialogue between the artist and the curator to create something outside of “show and tell.” For this exhibit you and curator Alex Harvey participated in a dialogue about your own work and the ICI archive. While I was perusing the Library two books in particular stood out, The Elements of Color and The Interaction of Color. In addition the curated selection of books there is a mesmerizing assortment of ephemera, of visual culture under a sheet of glass that didn’t possess a deliberate rhyme or reason but read like a visual tapestry. I recall a portrait of Michele Foucault, Earth particles, and vintage advertisements.

Ayeroff: Alex and I initially connected over the book I was reading when we met, a book that had been loaned to me by Lise Patt (the ICI Director) from the ICI library – The Songlines by Bruce Chatwin. Alex and I began speaking about belief, the desert and the structure of Chatwin’s history. The various objects on display in the library reflect the ideas we were working with. Each object was pulled because of a specific relationship – some because of their relationship to utopias, or the forms of utopia, or because they came into existence at the same time as Clarion.

Installation view of “Clarion Calls”, including from left to right:

“desires are already memories”, Hand-cut chromogenic print and Mylar

02272010-03022010, Super 8 films transferred to video

Courtesy, ICI and the artists

Moret: Clarion is a physical destination as a farm colony in Utah, but it also represents a state of being. What is the history that surrounds the location?

Ayeroff: The story goes that my family immigrated from Vilnius or Riga or another major city in the Russian empire around 1900.

Moret: And you are connected to Clarion though your great grandfather?

Ayeroff: I’ve been told that Nathan was a Buddhist – a member of the Jewish Labor Bund, a secular Jewish socialist party. My research lead me to statements made by Nathan declaring that he was indeed a founding member of Clarion.

Moret: What has your families’ reaction when you first expressed a desire to pursue the subject matter? How do they feel about the exhibition?

Ayeroff: The two generations of family that had lived in Clarion had died years before I began this work. However, the sons and daughters of the Ayeroff brothers and sisters born in Clarion were ready and willing to contribute. Everyone has his own story.

My father and I share this history. The work really belongs to him. He came with me on my second trip to Clarion. It was the first time he had ever been. A lot shifted on that trip. There was a lot of snow, a lot of quiet, a lot of just him and me. A lot of beauty. Expanse does that – it sets us city dwellers in our place.

Moret: Describe the process of culling archival photographs, maps, and information about Clarion.

Ayeroff: The University of Utah Library has a collection called the Jewish Oral History Project. It includes interviews conducted in the 1970s about Jewish life in Utah. Included in this collection is an interview with Nathan. I called the library, located the person who managed that collection and asked her to send me a copy of the transcript. A man in Salt Lake City published a book about Clarion in the mid ‘80s. The book contains a good mix of factual and anecdotal history. I spoke to family members, all a generation or two away from the Clarion colonists, collecting their stories.

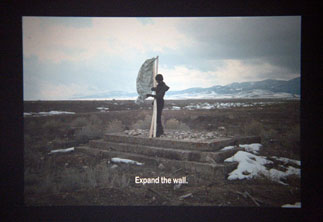

Arrive with a wall from 02272010-03022010, still from Super 8 film

Courtesy, ICI and the artists

Moret: I’m curious what prompted Clarion as a subject for your work.

Ayeroff: After I returned from Clarion the first time, I sat down to read a strange reprint of the original text of “Moving the Mountain” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman. I had happened upon this book having loved a few of her other works. All I knew was that it was a feminist utopian novel, which was more than enough to spark my interest. I opened to the title page and noticed the publication year – 1911, the same year Clarion was founded. The coincidence was too lovely. It marked the beginning of my understanding of Clarion as a utopia. After “Moving the Mountain,” I began reading the few published works about the colony that I could find. Simultaneously, I was reading Thomas More’s “Utopia,” Michel Foucault’s “Of Other Spaces,” Italo Calvino, Charles Fourier,” Calvino on Fourier.” I wanted to understand the utopian impulses my great-grandfather had inadvertently passed down to me.

Moret: When did you travel to Clarion for the first time?

Anna Ayeroff: The first time I ended up in Clarion was in 2008. My sister and I were driving from New York to Los Angeles. I had heard a bit about Clarion from family anecdotes. I knew I wanted to see the site where my grandfather was born and I knew that I wanted to take a souvenir from the site. I did not know that the approach of a pickup truck would spook us, sending us running back to the car, just at the moment I was picking up one of the bricks from the ruins. I ended up coming home with a brick in hand. Holding that brick – that was when the Clarion Calls project began. I spent the next two years researching, experimenting, reading, folding, writing, unfolding, printing, drawing – making images, making stories.

Moret: Did you return?

Ayeroff: In 2010, I returned to Clarion with more of a plan, although happenstance and whim had their influences as well.

Moret: You employ several mediums in your show- slides, super 8 film (transferred to video), photographs, and a sculpture. Super 8 film footage [transferred to video] of a road trip plays simultaneously on a wall opposite the slide projection. There’s a portion of the film where you appear holding a makeshift white flag, standing on top of a concrete platform. It’s a wonderful moment because it creates a bridge between the past and present and the land becomes the connective tissue between you and your great-grandfather. Do you know what function the platform served? Did you leave the flag there?

Ayeroff: It was the foundation of a building, probably one of the homes. The wall came home with me. I’ve called the action in that film Arrive with a wall. There are images from it also included in the slideshow. The flag is actually not a flag at all. It is a brick wall. The wall had to fold up and fit in my car. The wall was flimsy. It just blew in the wind. But I tried my hardest to keep the wall standing.

Moret: What did you encounter when you arrived?

Ayeroff: Clarion is a ghost town. You see mountains and expanse. You see tall weeds. In winter, you see unmarked snow. You hear cows from the dairy down the road. But it is nearly impossible to locate any site.

Moret: Were there any existing structures?

Ayeroff: All that remains are a few foundations from the buildings. Perhaps one was the school that they worked so hard to build for their children. Supposedly the ruins of the fallen cistern are still there somewhere far from the dirt road, although I have yet to find them.

Moret: There is an overwhelming sense in the show of hope and optimism. While Clarion failed as a sustainable colony unable to provide resources or adequate shelter for its inhabitants, it succeeded because of its undying effort to exist in the first place. The message of the founders of Clarion resonates within contemporary hearts and minds- the notion of making something out of nothing, emitting optimism when the odds are against you.

Moret: Throughout your great grandfather’s narrative there is mention that Clarion was a Utopia. What is your definition of utopia?

Ayeroff: Utopia is by definition both good place and non-place. The word was formed by Thomas More from the Greek roots ou meaning “not,” or homophonically eu meaning “good”, and topos, which means “place”. Utopia is a paradox by definition. This paradox does not keep a utopian from trying for utopia. A utopian is stubborn and he rarely knows he is one. As one who inherited the utopian gene, I believe that knowing as much as I can about failed utopias will allow me to solve the problem presented in this paradox.

Moret: How do you think it may be different from your great-grandfather’s vision?

Ayeroff: I don’t think that Nathan had a concept of utopia. What he was doing was just his reality – making a better life. Either his optimism or his ego got the best of him, got the best of all of them – they thought the colony would succeed, that’s all they could think.

Moret: A Mylar sculpture titled If I Could Live Here, I would is positioned as though it is coming through the window near the room’s ceiling. What does the shape represent?

Ayeroff: If I Could Live Here, I Would, is based on the form of a cosmic dust particle.

Moret: What about the form of the dust particle resonates with you?

Ayeroff: If I Could Live Here, I Would is my utopia. I knew that if I were going to make a utopia it would need to follow the good place/non-place paradox in order for it to exist. Calvino calls for “a utopia of fine dust.” I call for a utopia of fine dust so infinitely small and distant that my eyes will never see it. A cosmic dust particle seemed a place as close to a non-place as possible. The word cosmos coming from the Greek word kosmos meaning “order” but also “ornament” or “decoration”, a cosmic dust particle is ordered like a city, beautifully perfect in form and infinitely small in existence.

Moret: The Mylar is stitched, correct?

Ayeroff: Yes, each piece of the reflective Mylar is folded and hand sewn into clusters that are then sewn together into the large form.

Moret: Just as your great grandfather and the folks of Clarion did two generations ago, you constructed your utopia with our own two hands.

Ayeroff: Labor is a meditation on the future.

Moret: I’m curious what inspired you to incorporate a scientific practice in your work. Do you feel that you work is commenting on the role that science plays in art?

Ayeroff: Number has always held a strong spiritual significance for me. Number is what we use to order the world. Numbers are a cosmos, an ordered system. While I was looking for cosmic dust particles, I found a mathematician, Georg Cantor, who developed set theory, examining the actuality of infinity. The Cantor ternary set is a basic fractal pattern – a line segment divided into three parts, the center segment removed and this pattern repeated to the remaining line segments infinitely. The initiator and the first three iterations of this pattern are cut away in the first of the c-prints. The second c-print is based on the 2-dimensional square version of this set, called the Sierpinski carpet which (synchronistically) when created in multiple dimensions is called Cantor dust. The third c-print is cut in the fractal pattern called the Sierpinksi triangle.

Installation view of Alex Harvey and Anna Ayeroff’s work in ICI Laboratory

Courtesy, ICI and the artists

Moret: The Mylar is also injected in three color C-prints. Exacting shapes employed of rectangle, square, and triangle. The photographs share a common subject- the foundation that you stand on in the film. The photographs are taken at varying distances and degrees. Does the triad suggest past, present, and future? How did you determine the perspective from which you would photograph the landscape?

Ayeroff: The number three indeed holds a strong relationship to past, present and future time but moreover, for me, it signifies the arc of a story – beginning, middle, end. Three is the perfect number. It is the sum of its parts. It holds great significance in many mystical practices. The body of work that I have worked on since the completion of this version of Clarion Calls is actually based around the triangle and the number three’s significance in spiritual and ritual practices and beliefs. In the instance of these three hand-cut C-prints each photograph moves you closer in space to the ruins. The first, I built a shanty and I lived there for three years, is a long shot of the foundation within its landscape. The most photographic information is visible in this piece; the least amount of information is cut away. In the second piece, by returning to the desert he discovers himself, more of the ruins are visible but more information is removed. The third, by returning to the desert he discovers himself, the photograph is shot so close that the ruins’ textures are visible yet in the cutting more information is removed than is present. This play between information present and information removed is like the passing of history down over generations. As it moves through space and time, specific information becomes clearer, more visible but simultaneously the gaps get larger. For me, all that was left to do was fill the holes with hope – the Mylar of my utopia restored some of that unyielding optimism to the ruins.

Moret: The Project Room has found images that may have once appeared in an elementary science classroom, illustrating the Dust Particle tacked to the wall.

Anna Ayeroff: The prints are made from scans of a filmstrip found at the ICI. While looking through the archive we happened upon (with great excitement) a filmstrip that spoke about cosmic dust.

Moret: There is also a telescope with an incision made at the end that reveals a small screen of the exhibition space in elapsed time.

Ayeroff: The telescope belongs to the ICI archive, the hole included. It is a glimpse at the passing of time, the changing of light, a hidden, momentary step into another dimension.

Moret: There is an inextricable link between the Project Room and the Exhibition Space, turning the ICI space into one of interpretation, a living, breathing organism where work is created and displayed.

Anna Ayeroff: The ICI is a world of its own. With this installation, we’ve simply blended a few worlds – the ICI, Clarion and our own cosmic utopia.

Moret: What are your hopes for the remaining visions in the series?

Ayeroff: I hope the next curators locate things in the archive I’ve never seen, or help me to see things I’ve seen everyday in a different way. I look forward to seeing the interaction with the public – more visits, more dialogue. Mostly though I look forward to watching other thinkers at play.

Seeing through, video in telescope found in the ICI archive

Seeing through, video in telescope found in the ICI archive

Courtesy, ICI and the artists

|

A native Angelino, Moret spends her days wandering art spaces and writing in Moleskine notebooks. Her work has appeared in such publications as Art Works, ArtWeek, Art Ltd., Artillery, Art Scene, Flaunt, Flavorpill, For Your Art, THE, and The Los Angeles Times Magazine. She also created her own magazine “One Mile Radius” with photographer Garet Field Sells that explores the effects that the urban environ of Los Angeles has on artists and their work. To learn more visit www.byamoret.com |

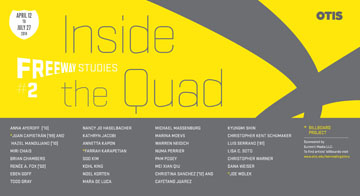

Freeway Studies #2:

Freeway Studies #2:

Seeing through, video in telescope found in the ICI archive

Seeing through, video in telescope found in the ICI archive

100/10∆1: Alex Harvey and Anna Ayeroff at the Institute of Cultural Inquiry (ICI)

100/10∆1: Alex Harvey and Anna Ayeroff at the Institute of Cultural Inquiry (ICI) Since its inception in 1991, The Institute of Cultural Inquiry has brought focus to the similarities and has questioned the accepted distinctions between the research processes of the arts and sciences. In this spirit, the ICI is pleased to announce the launch of an ambitious project: 100/10 (100 days/10 visions), which highlights the cross-disciplinary (or un-disciplinary) nature of knowledge production. Beginning January 31, 2011 and running for 100 consecutive (business) days, the ICI site and its archives will undergo a multitude of interpretations. Ten visual researchers—artists, writers, scientists, and other visual thinkers—will “play” with ideas that blend contemporary visual practices with aspects of the ICI Earth Cabinet, Ephemera Kabinett, and a 2,500+ volume library along with the ‘small display spaces’ of the eclectic and historically layered ICI space. To facilitate this project and to increase the possibilities for inversion and trickster curatorial strategies, the ICI site has been reconfigured to include many of the “institutional” forms the organization has often railed against. Visitors will find a “white box gallery,” a dedicated and well-stocked gift shop, and a clearly labeled library. At the same time, visitors will still find the unique, non-traditional features of the ICI laboratory– a time clock (with its adjacent punch cards) that clicks off the time of another (unidentifiable) time zone, a turning carrier for fractured postcards and other ephemera that operate somewhere between clues and evidence, a tattered Ephemera Kabinett with its ambiguously labeled drawers and constantly changing content and the many nooks and crannies that hide ICI treasures in plain sight/site. As a counterpart to our new “clean-space” gallery, we have also created a studio that will become the “messy-space” laboratory for our curators to configure their unique trajectories within the ICI body. Modeled on the transparent workspaces of 19th century natural history museums, visitors to the ICI will be able to glimpse research “in process.”

Since its inception in 1991, The Institute of Cultural Inquiry has brought focus to the similarities and has questioned the accepted distinctions between the research processes of the arts and sciences. In this spirit, the ICI is pleased to announce the launch of an ambitious project: 100/10 (100 days/10 visions), which highlights the cross-disciplinary (or un-disciplinary) nature of knowledge production. Beginning January 31, 2011 and running for 100 consecutive (business) days, the ICI site and its archives will undergo a multitude of interpretations. Ten visual researchers—artists, writers, scientists, and other visual thinkers—will “play” with ideas that blend contemporary visual practices with aspects of the ICI Earth Cabinet, Ephemera Kabinett, and a 2,500+ volume library along with the ‘small display spaces’ of the eclectic and historically layered ICI space. To facilitate this project and to increase the possibilities for inversion and trickster curatorial strategies, the ICI site has been reconfigured to include many of the “institutional” forms the organization has often railed against. Visitors will find a “white box gallery,” a dedicated and well-stocked gift shop, and a clearly labeled library. At the same time, visitors will still find the unique, non-traditional features of the ICI laboratory– a time clock (with its adjacent punch cards) that clicks off the time of another (unidentifiable) time zone, a turning carrier for fractured postcards and other ephemera that operate somewhere between clues and evidence, a tattered Ephemera Kabinett with its ambiguously labeled drawers and constantly changing content and the many nooks and crannies that hide ICI treasures in plain sight/site. As a counterpart to our new “clean-space” gallery, we have also created a studio that will become the “messy-space” laboratory for our curators to configure their unique trajectories within the ICI body. Modeled on the transparent workspaces of 19th century natural history museums, visitors to the ICI will be able to glimpse research “in process.” For the premier iteration of this ten-part project, 100/10∆1, the ICI has invited and collaborated with curator Alex Harvey to bring a number of rich and complex ideas to the “table.” At the center of his vision is Anna Ayeroff’s installation, Clarion Calls, a research-based exploration that draws parallels between utopias and history- both of which are rooted in the paradox of being a ‘better’ and ‘non-existent’ place. The display includes prints, sculpture, film and an 80-slide slideshow from which we are given a fragmentary story about a failed Jewish colony with a resident who shares the artist’s last name. Does the personal story and its nostalgic retreat underpin all studies of history and its documents? Harvey throws light on the single question that continually haunts the ICI archive. Ayeroff’s answer comes in the form of a large Mylar sculpture that invades the ICI space through an open window. The artist employs the form of a cosmic dust particle to build her own utopian place, integrating her abstract drawings and sculpture into the visual history of Clarion. By utilizing the fractal patterns of this celestial form, the artist revitalizes her photographs of a ruined past. If the call of family apocrypha initially brought Ayeroff to Clarion, Utah (study documents from that Interpretive Field Project are included in the ICI display) her laborious and repetitive re-mappings create a clarion call to the infinite “better world” possibilities that once drove the builders of these ruins.

For the premier iteration of this ten-part project, 100/10∆1, the ICI has invited and collaborated with curator Alex Harvey to bring a number of rich and complex ideas to the “table.” At the center of his vision is Anna Ayeroff’s installation, Clarion Calls, a research-based exploration that draws parallels between utopias and history- both of which are rooted in the paradox of being a ‘better’ and ‘non-existent’ place. The display includes prints, sculpture, film and an 80-slide slideshow from which we are given a fragmentary story about a failed Jewish colony with a resident who shares the artist’s last name. Does the personal story and its nostalgic retreat underpin all studies of history and its documents? Harvey throws light on the single question that continually haunts the ICI archive. Ayeroff’s answer comes in the form of a large Mylar sculpture that invades the ICI space through an open window. The artist employs the form of a cosmic dust particle to build her own utopian place, integrating her abstract drawings and sculpture into the visual history of Clarion. By utilizing the fractal patterns of this celestial form, the artist revitalizes her photographs of a ruined past. If the call of family apocrypha initially brought Ayeroff to Clarion, Utah (study documents from that Interpretive Field Project are included in the ICI display) her laborious and repetitive re-mappings create a clarion call to the infinite “better world” possibilities that once drove the builders of these ruins. Harvey’s display illuminates the struggle between form and content that “troubles” any archive – be it a collection of stories, a chest of documents or an assortment of shapes we imagine might build a “perfect world.” A series of displays throughout the library and in other ICI “small spaces,” will engage visitors with Harvey’s complex and multi-layered ideas. Also on display is a print portfolio that includes lithographs by Ayeroff including prints made from filmstrips found in the ICI Ephemera Kabinett.

Harvey’s display illuminates the struggle between form and content that “troubles” any archive – be it a collection of stories, a chest of documents or an assortment of shapes we imagine might build a “perfect world.” A series of displays throughout the library and in other ICI “small spaces,” will engage visitors with Harvey’s complex and multi-layered ideas. Also on display is a print portfolio that includes lithographs by Ayeroff including prints made from filmstrips found in the ICI Ephemera Kabinett.